I am currently writing a manuscript for publication in a peer-reviewed molecular biology journal. And I’m hating it (just a little). Hopefully I’ll have this out of my hair in just a few more weeks. But it occurred to me, not all of my readers are scientists (indeed, based on the commenters alone, I would say that only a few of my readers are scientists). It occurs to me that not all of my readers know exactly how peer-review works – and why it’s the best game in town for verifying scientific work (well, aside from replication of the results by an independent lab).

I am currently writing a manuscript for publication in a peer-reviewed molecular biology journal. And I’m hating it (just a little). Hopefully I’ll have this out of my hair in just a few more weeks. But it occurred to me, not all of my readers are scientists (indeed, based on the commenters alone, I would say that only a few of my readers are scientists). It occurs to me that not all of my readers know exactly how peer-review works – and why it’s the best game in town for verifying scientific work (well, aside from replication of the results by an independent lab).

So I thought I would write a little bit about how it works from the inside. The experiments that I’m writing about have been conducted over the last several years by another post-doc in the lab and I. We were working on different problems, but as it turns out, together our data shows several neat things about a protein that we study.

So. He and I have spent the last several months fighting about what belongs in the paper, and what doesn’t. Sorting the wheat from the chaff. And if he doubts any of my experimental findings, I do extra experiments to convince him. And vice versa. So over the last few months we’ve hashed out a story that we think some folks will find interesting. And we’ve managed to convince each other that this story is probably true.

But it doesn’t stop there. Next, I’ve been writing off and on over this time (and much more intensively more recently). I’ve also organized and integrated our data together into figures that are more intuitive than if I presented our data as it arrived chronologically. I gave a lab meeting just before Christmas, and had everyone in the lab look at the figures. As it happens, they hated them. They found them unclear, and at times, unconvincing. So I added a couple of experiments, and removed a couple that folks found unconvincing (so now I won’t make a couple of the conclusions I wanted to make – but I can do more on that later, and put it into a different paper).

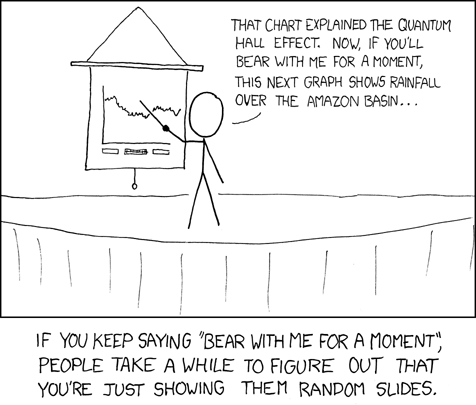

I’m nearly at the point where I’ll hand out the manuscript and heavily revised figures to a few folks that I think are talented. These aren’t folks who are going to say, “Yes, Dr. Dr. Factician, this is the most brilliant piece of work I’ve ever seen” or “I agree with you 100%, you brilliant hunk of man, you!” Rather, I’ll hand it out to people who both don’t care what I think and have the intellectual fortitude to tear up the paper. Hopefully these folks will be ruthless with it, and help me make it into an even better paper.

After those revisions, I’ll give it to my advisor. I’ve only written one paper with her in the past. She is fairly particular about what goes and what doesn’t. More than likely, she’ll want to see 5 or more drafts of the paper before she’s happy (keep in mind, by the time she sees it, this paper will have been through more than 30 drafts).

After that, I clean up the paper one last time, checking for typos, casting about for logical errors, and off it goes to the journal. At the journal, it goes through 2 types of review. The first review is by the editorial staff. They will read the paper and decide if it’s proper material for their journal (i.e. topical) and if it’s sexy enough. There’s not much that I can do about sex appeal – that’s a pretty subjective area. Granted, I’ll try to make my work sound as interesting as possible, but hand it to 3 different people, 1 will say it’s Super-Sexy, 1 will say it’s interesting and 1 will say it’s banal tripe.

So, supposing I make it past the editor, it will be sent to 3 ad hoc reviewers. These are folks who are experts in my field. People in the position of my advisor (professors and the like at major medical schools). My advisor often gets me to review papers for her, so it’s possible my paper will get reviewed by post-docs, but it will be reviewed by people in my field. All 3 of them have to think that the paper is interesting and that the science is solid. Any one of them is sufficient to torpedo the paper.

Finally, if my paper is accepted, it will be printed in a journal for everyone to see. If there are problems with it, we will hear about it in other peoples’ papers. If it fits with other peoples’ data, and helps them to do other experiments in the field, they will cite my paper in their own papers, raising the visibility of my paper. (For example, my most successful paper has been cited 128 times).

So briefly, about a dozen people in my lab have criticized my work, and helped me make it better. Mrs. Factician has also played a large role in cleaning up my work. Several other scientists in my department will look at my paper. My advisor will read it and criticize it. An editor at the journal will read it and criticize it. Three ad hoc reviewers will read and criticize it. And finally, it will be placed in a journal, where many thousands of scientists can read and criticize it.

One bit of advice I give to starting graduate students: If you give your work to someone to read, and they say, “That was fantastic, don’t change a thing” you’re talking to the wrong person. You want the person who will say, “And on page 2, I can’t believe you started this sentence with the phrase X. It’s simply not true!”. Better to be criticized heavily by your colleagues close to home, and get your game in shape before sending it out for review.

Today's Friday beautiful science comes from the Mercury Messenger mission:

Today's Friday beautiful science comes from the Mercury Messenger mission: